AI risks making global inequality worse

Ctrl+Alt+Elite

This post was originally published on 4 July 2025.

At the AI table, or on the menu

Every few years, a wonder-gadget arrives promising to “rescue” the Global South—remember the $100 laptop, the gravity-driven water pump, or the soccer ball that generated electricity? Each invention was pitched as a shortcut around structural problems; each fell short of promises.

The AI for Good Global Summit—taking place next week in Geneva—is billed as “the United Nations’ leading platform on Artificial Intelligence to solve global challenges.” The event feels déjà-vu. As Silicon Valley sprints to “move fast and break things” with AI, policymakers scramble to answer a trillion dollar question: Will AI work as a true utility—powering health clinics, schools, and local businesses across Africa—or will it mainly accelerate back-office efficiencies for firms headquartered elsewhere, deepening the digital fault-line?

The stakes are high. If African voices aren’t at the design table, the systems that decide credit scores, diagnose diseases, or educate future generations could simply automate yesterday’s biases at scale. Below, we unpack who is setting the rules of the new utility, who stands to gain, and what will happen if Africa isn’t a co-architect in the age of AI.

— Joe Kraus, Aftershocks Editor

3 things to know

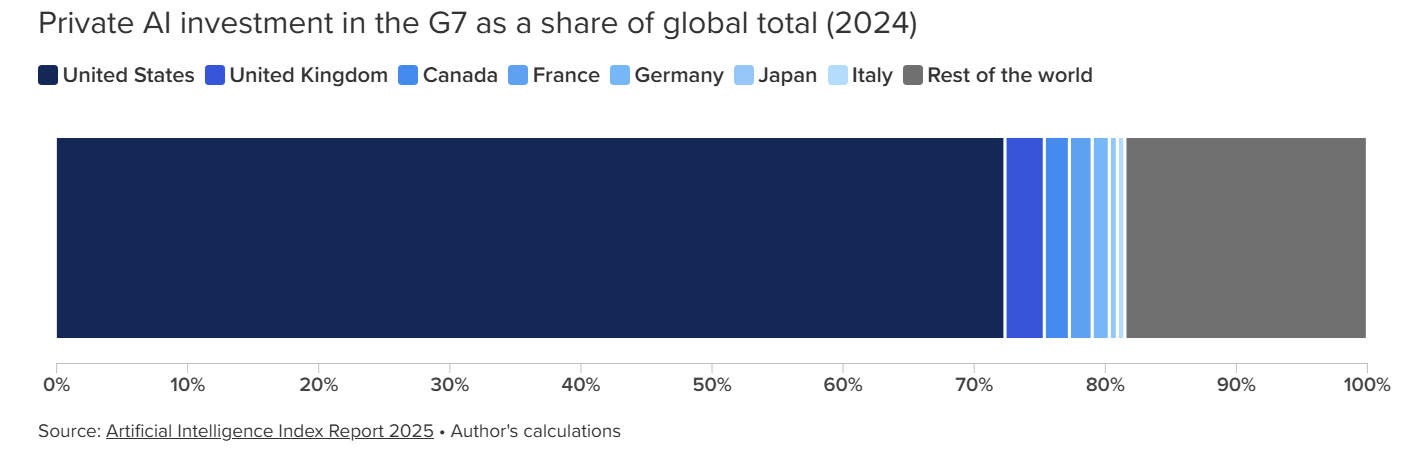

AI investment risks perpetuating global economic inequality. Over 80% of private AI investment in 2024 was in G7 countries. Another 6% was in China. Just 0.05% was in Africa’s 54 countries, combined. Of the more than 2,000 newly-funded AI companies last year, just nine were in Africa: South Africa (4), Egypt (2), Cameroon (1), Nigeria (1), and Tunisia (1). Oh, and the US and China hold 60% of all AI patents.

Source: The Atlantic Council

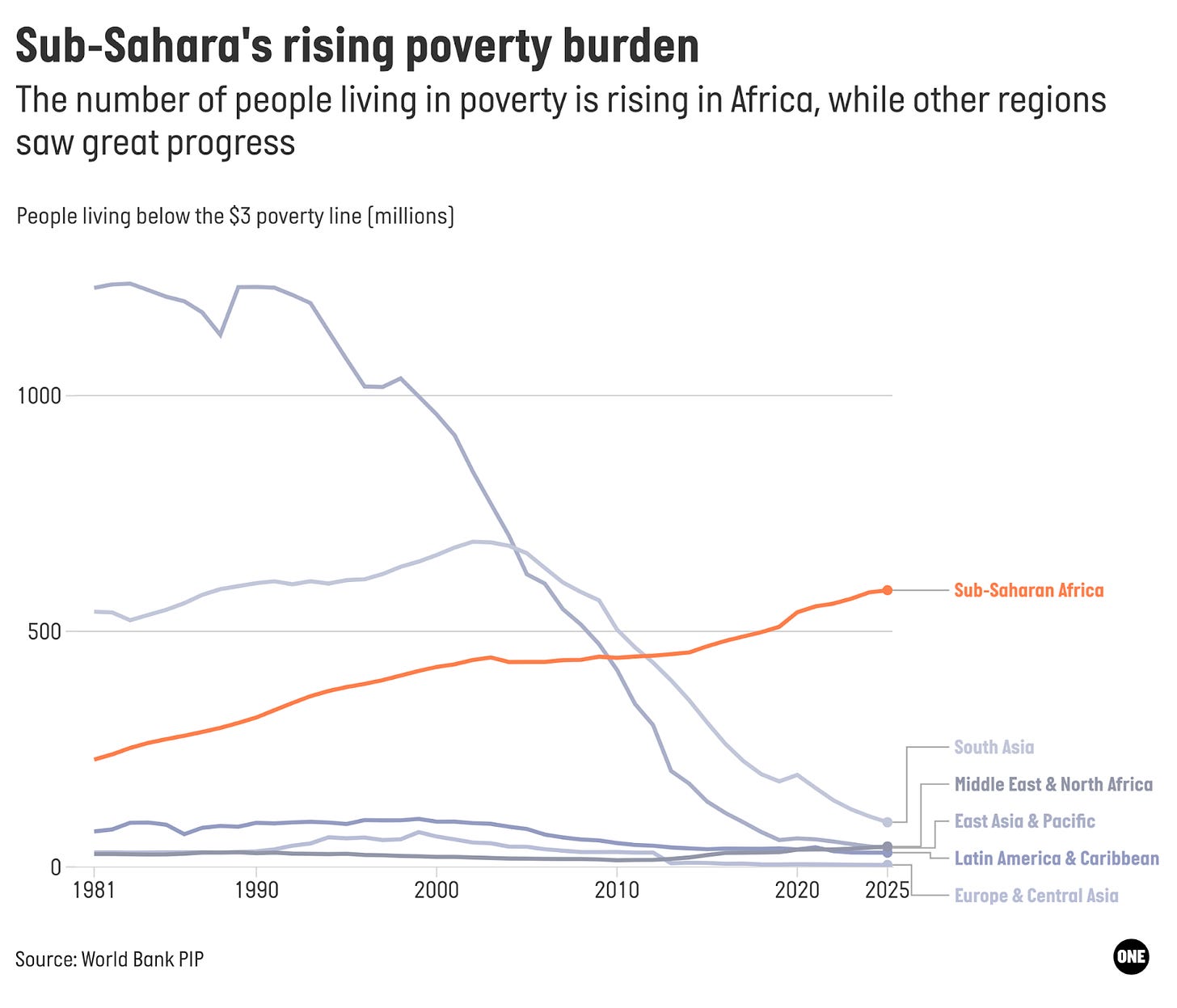

Why it matters: Rich countries stand to be the big winners of the AI race. And the prize is massive: The global AI market is expected to surge to $4.8 trillion by 2033, a 25-fold increase in just a decade. That will further entrench economic inequalities as the rich get richer and the rest get left farther behind. That doesn’t bode well for Africa, where poverty levels continue to rise while falling elsewhere. And in a dark irony, much of the underlying work behind AI systems is done by underpaid laborers in developing countries exposed to toxic content.

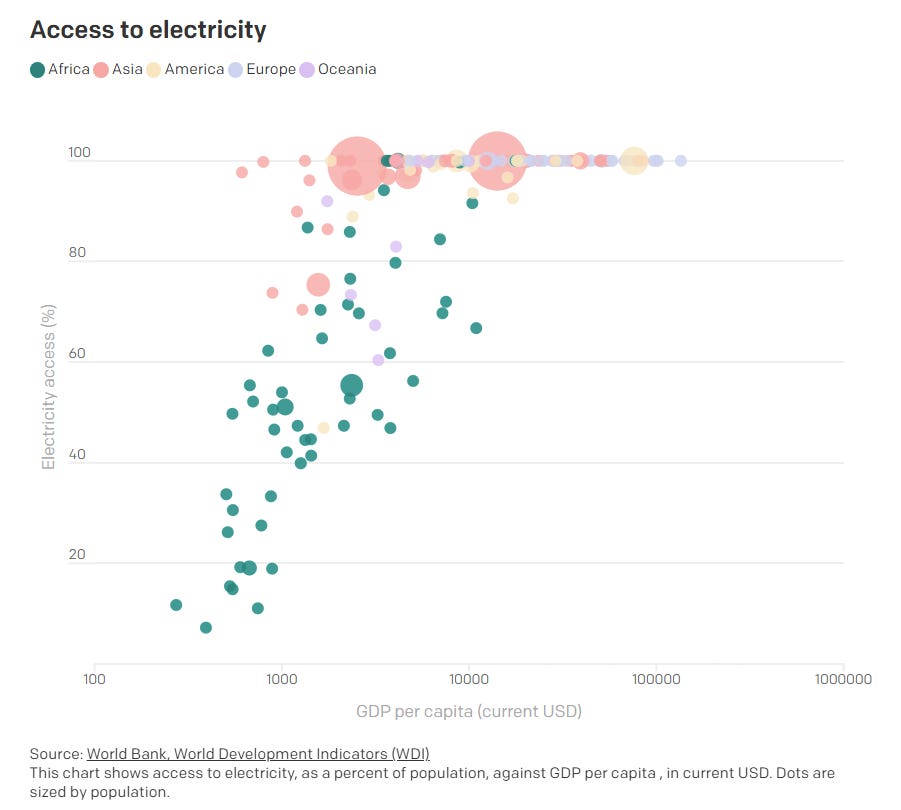

Africa is not AI-ready. AI requires massive amounts of electricity. Many African countries struggle to meet their current electricity needs. 605 million Africans (44%) do not have access to electricity. For those that do, access is often unreliable and inadequate: In a year, the average Nigerian uses less energy than an air conditioner in the US.

Source: ONE Data

Why it matters: Africa’s energy demand is expected to nearly double by 2040, as populations grow and living standards improve. By then, 90% of the people lacking electricity will live in Africa. It is unclear how—or if—African countries can quickly scale up the energy infrastructure needed to power AI centres and compete with countries that already have the necessary infrastructure in place.Africa’s absence from AI’s design locks in biases. AI systems are built on existing data and information, some of which includes stereotypes and racist language and images. AI reproduces and perpetuates those biases. In 100 images of “an Indian man” using a popular generative AI text-to-image system, nearly all featured an old man with a beard and turban. Similarly, a search for “a Nigerian person” produced highly homogenous results, despite Nigeria having hundreds of distinct ethnic groups and cultures.

100 images of “a Nigerian person” using the AI system MidjourneySource: Rest of World

Why it matters: Generative AI systems are designed to mimic what has come before. They do that by synthesising mountains of data. The biases in that data—or present in the humans helping design AI systems—invariably get baked in. It’s a tough problem to fix. It becomes exponentially tougher if the people and companies designing AI systems don’t represent the full breadth of the human experience, or aren’t transparent about the data they use and how they train their systems. Companies can’t claim to be developing “AI for all of humanity” if countries and entire groups of people are excluded.

FROM THE ONE TEAM:

David McNair argues for reimagining the purpose of development and development finance to move from scarcity to security.

David published a piece in the Independent newspaper calling for a new approach to thinking about aid – not as charity but as mutual investment.

ONE’s data team is working with Google to make it easier to access and analyse the world’s public data. Here’s why that’s important.

Reuters featured ONE’s data visualisation on aid cuts.

Micaela Iveson with six “vax facts” in 60 seconds.

IN THE QUEUE:

The development sector isn’t broken, it was built brittle.

The US aid cuts could kill an estimated 14 million people by 2030.

In Sudan, doctors say US aid cuts have been fatal.

Climate change could ignite the next financial crisis.

Chinese EVs are dominating Kenya’s EV market.

The ONE Campaign’s data.one.org provides cutting edge data and analysis on the economic, political, and social changes impacting Africa. Check it out HERE.